Food for Thought

If there’s one thing I learned while researching and writing The Story of Sushi, it’s that the history of sushi has been one of surprisingly constant change and evolution, both in Japan and internationally. The book’s subtitle isn’t “An Unlikely Saga of Raw Fish and Rice” for nothing.

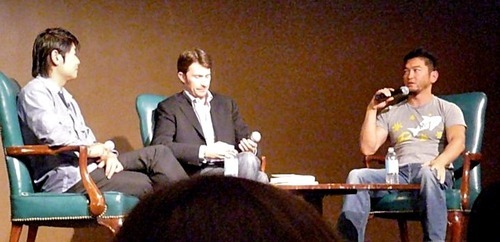

The other day I had the honor of hosting a sold-out panel discussion at the Museum of the City of New York on the evolution of sushi with two talked-about young sushi chefs in the region: Bun Lai of Miya’s Sushi in New Haven (above right) and Hiroji Sawatari, an alumnus of the legendary New York sushi house Yasuda and future chef at the anticipated new SoHo eatery Niko, slated to open this fall (left). These two sushi chefs couldn’t have been more different.

Though relatively young, Hiroji is of the seriously old-school variety of sushi slinger. He began his apprenticeship in Japan at age 16 and brought his sushi-making skills to the U.S. at 21, where he spent four years at the highly-regarded Hatsuhana before returning to the very heart of the Japanese sushi world – the enormous Tsukiji Fish market in Tokyo – to hone his skills further for a year at Sushi-Iwa, a half-century-old shop located just steps away from the world’s clearinghouse for the freshest fish. Back in New York he worked his way up through chef positions at Sharaku and Megu in TriBeCa to a four-year stint at Sushi Yasuda. Last year he joined Food Network star Iron Chef Morimoto at his flagship Japanese eatery in Philadelphia.

Bun, meanwhile, is altogether different. The son of a Chinese father and Japanese mother, he lived in Japan as a boy, watching his Japanese grandmother pickle plums and cucumbers and prepare traditional Japanese fare including fresh fish. But the family moved to Connecticut, where Bun’s mother opened Miya’s in 1982, the first sushi bar in the area, and Bun grew up mostly Americanized. Bun’s mother still oversees the restaurant, but today Bun is the mastermind of its new incarnation, and his charismatic and unconventional approach to sushi, its ingredients, and its presentation has quickly transformed Miya’s into one of the most talked-about sushi restaurants around.

Bun conceives of his work at Miya’s as the logical progression of sushi as it inevitably evolves into food that is cross-cultural, and while his menu is unconventional, his lively interactions with customers also revive the traditional relationship between a sushi chef and his clientele. Bun considers himself both a social and environmental activist, and has transformed Miya’s into the first sushi restaurant on the East Coast to integrate sustainability criteria for the seafood it serves. (Bun is also the 2010 recipient of Key to the City of New Haven for his contributions to the community.)

A few days later I had the chance to visit Bun at Miya’s for dinner. Here we are, pictured above, as he studiously reads what he claims is one of his favorite books, The Secret Life of Lobsters – which was sitting on the sushi bar, with many other books, when I arrived. An example of Bun’s activist menu: we ate these tiny fried crabs, which he features because they are not just yummy, but a pesky invasive species. Now there’s a meal you can feel good about.