The Surprising History of Tuna in Japan

Today, bluefin tuna is considered the pinnacle of fine sushi, especially bluefin toro–the fatty belly cuts of the fish. This is kind of funny, because just a few decades ago the Japanese considered toro such a disgusting part of the tuna that the only people who would eat it were impoverished manual laborers. And prior to about the 1920s, no self-respecting Japanese person would eat any kind of tuna at all if they could possibly avoid it. Tuna was so despised in Japan that all tuna species qualified for an official term of disparagement: gezakana, or “inferior fish.”

Today, bluefin tuna is considered the pinnacle of fine sushi, especially bluefin toro–the fatty belly cuts of the fish. This is kind of funny, because just a few decades ago the Japanese considered toro such a disgusting part of the tuna that the only people who would eat it were impoverished manual laborers. And prior to about the 1920s, no self-respecting Japanese person would eat any kind of tuna at all if they could possibly avoid it. Tuna was so despised in Japan that all tuna species qualified for an official term of disparagement: gezakana, or “inferior fish.”

In the old days in Japan, if you had no choice but to eat tuna you’d do everything you could do get rid of the bloody metallic taste of the fresh red meat. One trick was to bury the tuna in the ground for four days so that the muscle would actually ferment, which led to tuna being called by the nickname shibi–literally, “four days.”

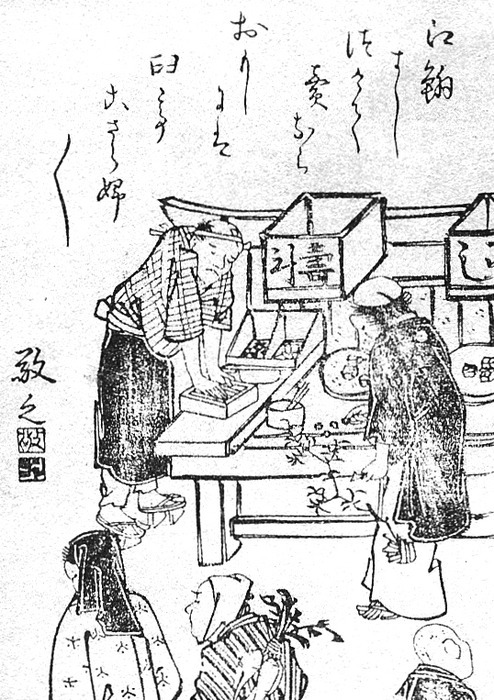

Not until the 1840s did an unintentional bumper crop of bluefin in Japan cause sushi makers to try to sell the fish at all, and these were rather pathetic street vendors catering to the lowest classes. They did their best to mask the inherent flavor of the flesh by smothering the red flesh in soy sauce and marinating it for as long as possible. Even today, purveyors that handle bluefin may soak it in ice water all night in an attempt to expunge the less desirable components of the fish’s smell.

The arrival of refrigeration technology made it possible to distribute tuna more widely, and as people gradually grew used to seeing the red meat of tuna on sushi, disdain for the fish decreased. But the fatty cuts of the fish were still considered garbage. There are reports that tuna belly was a common ingredient in Japanese cat food.

After World War II, with the American Occupation and the influx of Western culture into Japan, the Japanese began eating a more Westernized diet, including red meat and fattier cuts of it, which paved the way for the acceptance of tuna and toro in more recent decades in both Japan and the West.

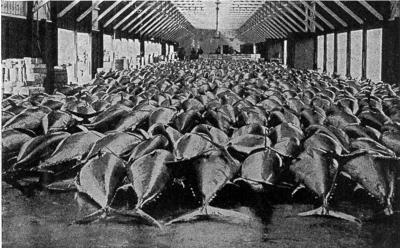

But the current bluefin fad–Atlantic bluefin in particular–remains a historical anomaly, and one partly manufactured deliberately, for corporate profit. During the heyday of Japan’s export economy, Japanese airline cargo executives promoted Atlantic bluefin for sushi so they’d have something to fill their planes up with on the flight  from East Coast US cities back to Tokyo. And as the recent documentary film The End of the Line has reported, Mitsubishi Corporation, one of the largest bluefin distributors in the world, now appears to be stockpiling massive amounts of bluefin in enormous high-tech deep freezers so it can make a killing dolling them at inflated prices out after the wild fish is all but gone.

from East Coast US cities back to Tokyo. And as the recent documentary film The End of the Line has reported, Mitsubishi Corporation, one of the largest bluefin distributors in the world, now appears to be stockpiling massive amounts of bluefin in enormous high-tech deep freezers so it can make a killing dolling them at inflated prices out after the wild fish is all but gone.

Back in Japan you can still find a few old-school sushi aficionados who disdain bluefin toro. They’ll tell you that toro is child’s play. Anyone can enjoy that simplistic, melt-in-your-mouth succulence, they say. It takes the real skill of a connoisseur to appreciate the more subtle and complex tastes and textures of the traditional kings of the sushi bar–delicate whitefish like flounder and sea bream being some of the best, along with mackerels, jacks, clams, squid, and other types of shellfish that have been popular all along. Personally, I won’t eat bluefin anymore, and I don’t miss it at all. My sushi eating experiences have actually become more interesting as a result.

This post was first published on The Atlantic.