The Magic of Buddhism

One of the most important Buddhists in the East is completely unknown in the West. And he wasn't into Zen meditation.

by Trevor Corson

Kyoto Journal

Originally published in the summer 2000 issue.

Mention Buddhism and we conjure up robed monks removed from mundane matters, meditating in remote Zen temples or Tibetan monasteries. It is easy to forget that dramatic differences separate Zen practice from Tibetan, and that many Buddhists in history have meddled actively in secular matters. And though Buddhism is often appreciated as a philosophy that satisfies spiritual needs without the baggage of deities and faith, it can also be very much a religion—replete with gods, offerings, spells, and magic.

In Japan, Zen is the Buddhism that has most come to define our impression of Buddhist practice: silent, detached, philosophical. But Zen was a relative latecomer in Japanese history. Strains of Buddhism closer to the Tibetan variety were brought to Japan hundreds of years earlier, and like Tibetan Buddhism they were "tantric," emphasizing not quiet meditation but mystical magic. Gaudily sculpted idols from a populous pantheon of deities, raucous chanting and drumming, impossibly complex contortions of esoteric movements, arrays of intricate implements and paintings, and great quantities of fire and smoke are the hallmarks of tantric Buddhism—a closely guarded technology employed to, among other things, heal disease, end drought, and vanquish enemies.

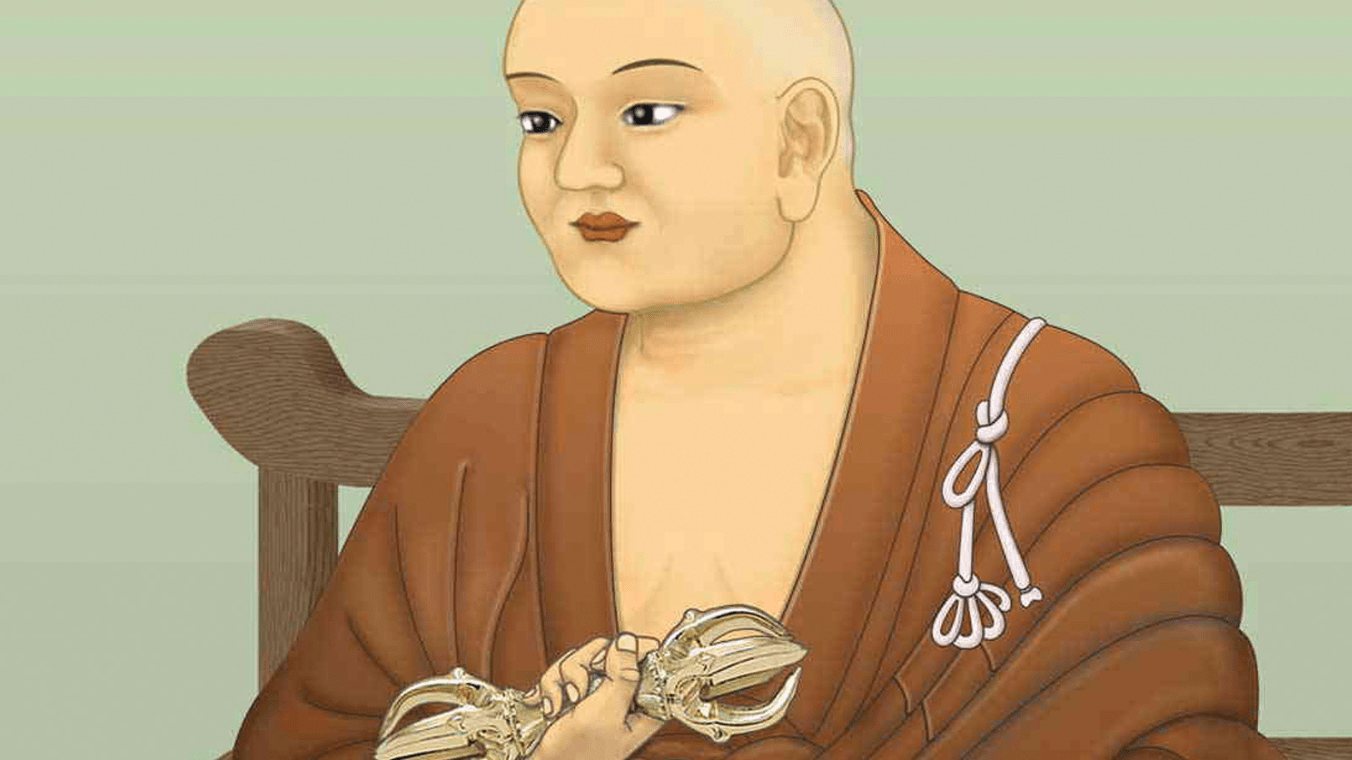

The most concentrated form of tantric Buddhism in Japan is called Shingon, a sect founded in the ninth century by a young prodigy of a priest named Kukai. During the Heian Period (794–1185), when native Japanese culture first flowered in the city of Kyoto. Kukai's shrewd alliance with the imperial court catapulted Shingon to the status of Japan's de facto state religion. Today, Shingon continues to claim as many adherents in Japan as Zen. Shingon's noisy, fiery rituals are still performed behind closed temple doors to ward off sickness, welcome wealth, help with examinations and business ventures, and assuage hungry ghosts. Shingon means "true word," a reference to the loud chants—mantras—central to tantric practice.

Hundreds of books on Shingon have been published in Japanese, but Kukai and his sect remain virtually unknown to the West. This is a striking omission, since in Japan Kukai is one of the most deeply revered figures in the nation's history. Westerners finally get an intimate look at this extraordinary priest in a new study of Kukai's career: The Weaving of Mantra, by Columbia University professor Ryuichi Abe.

Abe is a scholar of religion in New York City but he hails from a respected Shingon temple family in Tokyo. His father and brother are both Shingon priests; Abe himself knows the secrets of esoteric Shingon training. Yet Abe's scholarship sometimes irks his scholar-priest colleagues back in Japan. That is a good sign. Irreverent enough to seek the real Kukai lurking under the legends, Abe exposes the elements of an engrossing story.

Born in 774, the young Kukai was being groomed to enter the Confucian imperial bureaucracy when his high-ranking relatives were implicated in an assassination plot, their target the Emperor's deputy. Kukai's hopes for success dashed, the boy dropped out of college and wandered the forests as a Buddhist recluse. After a decade of obscurity the frustrated Kukai took a terrible risk and made the perilous journey to China in search of the latest tantric teachings. He soon returned to Japan triumphant, armed with a new kind of Buddhism systematized around an esoteric strain of secret ritual. By the time he died in 835, Kukai had achieved sweet vindication for his thwarted career. From a no-name monk Kukai had himself risen to become a deputy to the Emperor—a kind of magico-religious minister of health, agriculture, and defense combined.

Kukai's stunning rise to power is usually attributed by scholars to his deep spirituality. The emperor, they explain, was tired of meddlesome monks and needed a priest who would stay out of court politics. Similarly, historians assert that during the Heian period in the city of Kyoto, as native Japanese culture began to flourish, Buddhist practice evolved from superstitious magic toward a more mature quest for enlightenment—à la Zen meditation. Abe helps to set the record straight. The Weaving of Mantra reveals how Kukai spun religion for purposes that were partly political, and shows how similar Kukai's new sect was to the Zen Buddhist practice already popular in Japan: magical technologies for influencing the world—not for escaping from it—that would continue to dominate Japanese religion for centuries.

Abe has helped rescue Shingon from the dictates of sectarian debate in Japan and from an inflated emphasis in the West on Zen. But sadly Kukai, Japan's most popular priest, will remain enshrouded for Westerners by Abe's ploddingly academic presentation. Moreover, the author's scrupulousness is admirable but it also undermines his courageous conclusions. Abe argues that Kukai emphasized secret ritual in order to ensure Buddhism's independence from the Confucian government. The opposite seems a more likely conclusion and is supported by the evidence. As a frustrated young Confucian, Kukai might well have decided to systematize a new kind of secret Buddhist ritual and magic because it gave him a monopoly on political power with which to earn the patronage of the Emperor himself.

Ultimately Abe, even with his own Japanese Buddhist background, falls prey to the modern Western urge to separate church from state, religion from politics, meditation from magic—one sacred and the other profane. Kukai himself would probably not have understood these distinctions. For Kukai, Buddhist enlightenment affirmed the magic of mundane matters—perhaps more than it ever will for us. ❦